Short film programme: Structural film (1963-1972)

Tuesday 30th of May, 6pm in the Richard Hoggart Building cinema (room 104)

Join us on Tuesday the 30th of May at 6:15pm (doors open at 6pm) for an evening of structural short films. The total run time of the films is 2 hours 14 minutes, so with short breaks in between the programme should finish by around 8:45pm.

The programme for the evening is as follows:

Lemon (1969, Hollis Frampton). 7 minutes.

(nostalgia) (1971, Hollis Frampton). 36 minutes.

Mothlight (1963, Stan Brakhage). 3 minutes.

La Chambre (1972, Chantal Akerman). 11 minutes.

Wavelength (1967, Michael Snow). 45 minutes.

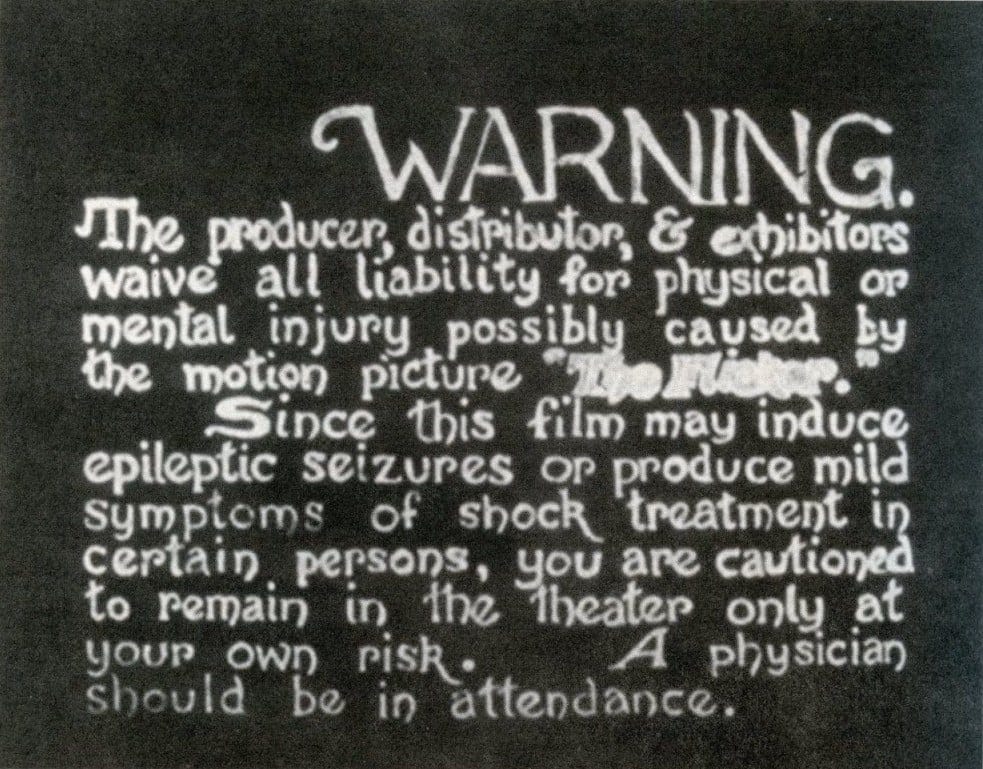

The Flicker (1966, Tony Conrad). 30 minutes. Note: this film has been known to produce adverse reactions in viewers.

Structural film was a key movement of avant-garde/experimental film which rose to prominence in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, arguably closer to conceptual art than to mainstream cinema, founded on a rejection of narrative, a focus on abstraction and formalism, and an interest in using film to ask self-reflexive questions about the nature and effects of film representation itself. Below is a short introduction to each of the films that will be shown.

Lemon (1969, Hollis Frampton) is a 7-minute film of a lemon as a light moves slowly over it. In Frampton’s words, “As a voluptuous lemon is devoured by the same light that reveals it, its image passes from the spatial rhetoric of illusion into the spatial grammar of the graphic arts.” This film has been chosen as a palate-cleansing introduction to structural film and its typical concerns with the nature of film and film aesthetics, and the relationship between appearance and perception. The film can be seen as a short study in the transformation of a physical commodity into an image-commodity, and in this sense read alongside Andy Warhol’s work of the same period, or Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, according to which, “in societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.”

(nostalgia) (1971, Hollis Frampton) is a 38-minute film consisting of 12 static shots of 12 still photographs burning to ashes on a hot plate, accompanied by a voiceover describing their contents. But the voiceover describes the photograph that will appear in the next shot, meaning the first visible photograph is unexplained and the last described is unseen. Part of Frampton’s Hapax Legomena series, (nostalgia) is one of the most accessible of Frampton’s works. For more about Frampton, see Ed Halter’s 2012 essay for the Criterion Collection, “A Hollis Frampton Odyssey: Nostalgia for an Age Yet to Come”.

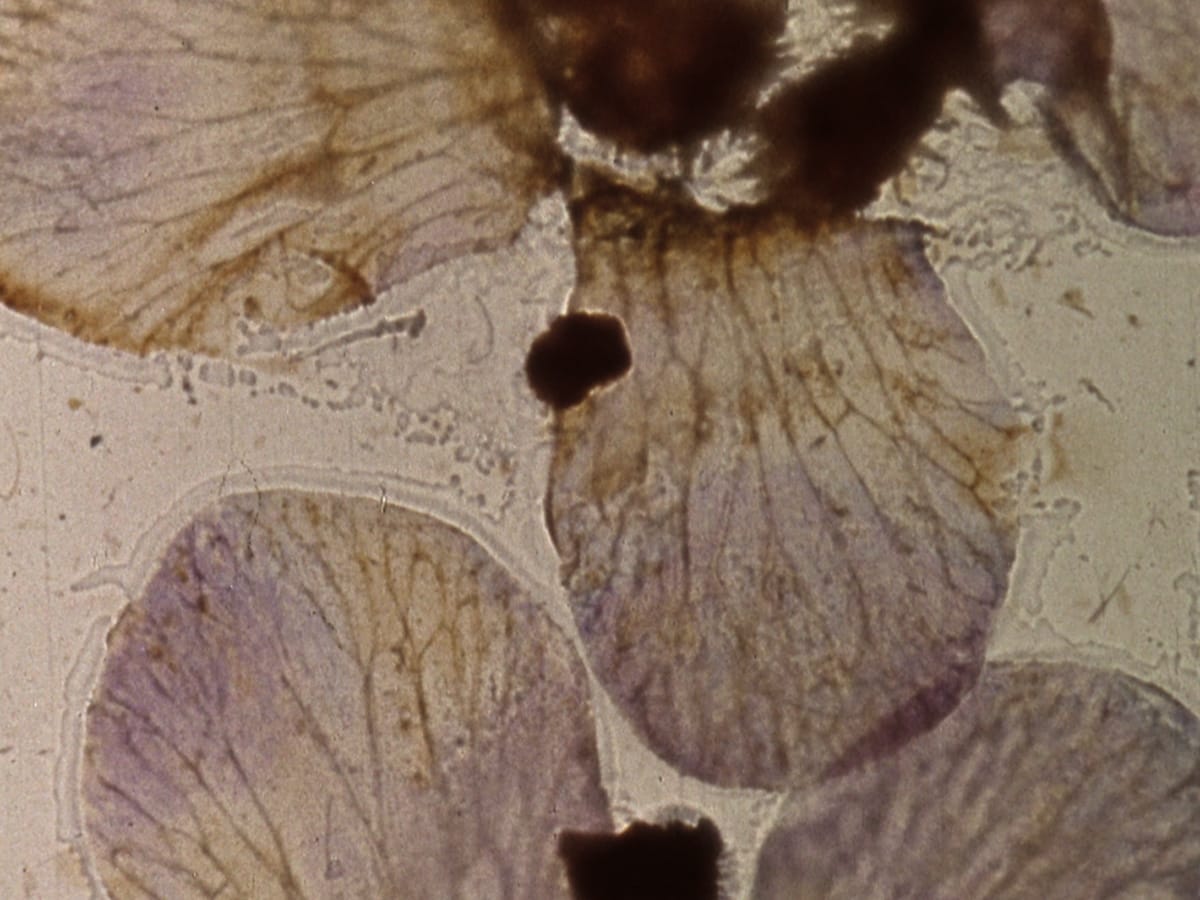

Mothlight (1963, Stan Brakhage) is just 4 minutes long, constructed from shots of moth wings, flower petals and blades of grass, pressed between 16mm splicing tape. Brackhage isn’t, strictly speaking, a structural filmmaker; in fact, structural filmmaking can be seen as an attempt to move away from Brackhage’s style.

His influence on the movement, however, is evident. If the structural filmmakers aim to dismantle the illusionistic tendencies of filmmaking, Brackhage seeks to reanimate his subject. Of course, with no celluloid, this isn’t really a film at all, but a projection. In such a conceit, Brackhage returns our focus to the act of projection and the production of the image (whether or not he wants to). For more on Mothlight see J. Hoberman’s 2012 essay in Artforum.

La Chambre (1972, Chantal Akerman) is an 11-minute ‘moving still life’ depicting Akerman in her small apartment in New York, the first film she made in the city where she would go on to create masterpieces like News From Home (1976). See here for Sight and Sound magazine’s list of 10 essential films by Akerman.

At 45 minutes long, Wavelength (1967, Michael Snow) is the longest film in our programme. Widely considered one of the greatest avant-garde films ever made, Wavelength has almost no action or plot, and consists of a single, static, gradual zoom shot inside a studio loft. The film is instead an examine of the relationship between vision, sound and perception, and the possibility of film to create perceptions unachievable in real life by the human eye. In this sense, it is an examination of cinema and photography as new kinds of human perception, much in the vein of Walter Benjamin’s ideas in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. For more about the film, see this short piece about the film on the Art Canada Institute’s website by Martha Langford from her book about Michael Snow. For more about Michael Snow, see this short biography.

One of the most challenging and provocative structural films, Tony Conrad’s film The Flicker (1966) is exactly what it sounds like: a 30 minute flickering screen. The film experiments with stroboscopic effects, alternating black and white frames at different intervals. Viewing is initially intense, but between the frames patterns seem to emerge: scratches and textures in the film, repetitions of frames; some viewers report seeing, shapes, movement and even colours.

Epilepsy warning: the film features strobing light